writing light

translated with Goggle traduction

Charlie in front of the train station

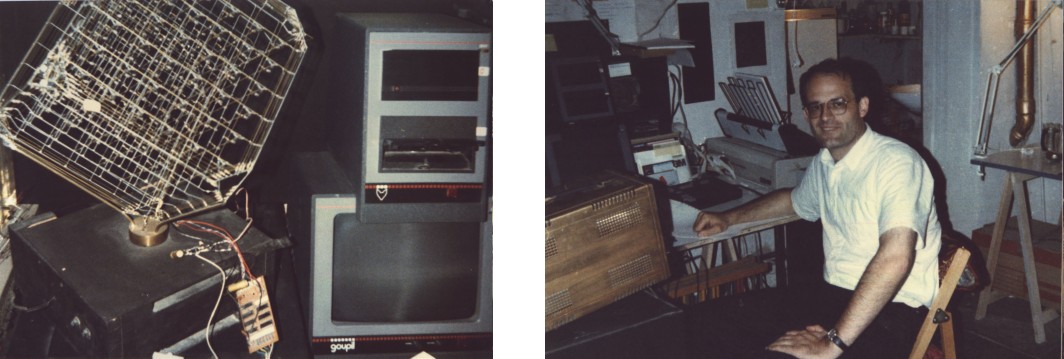

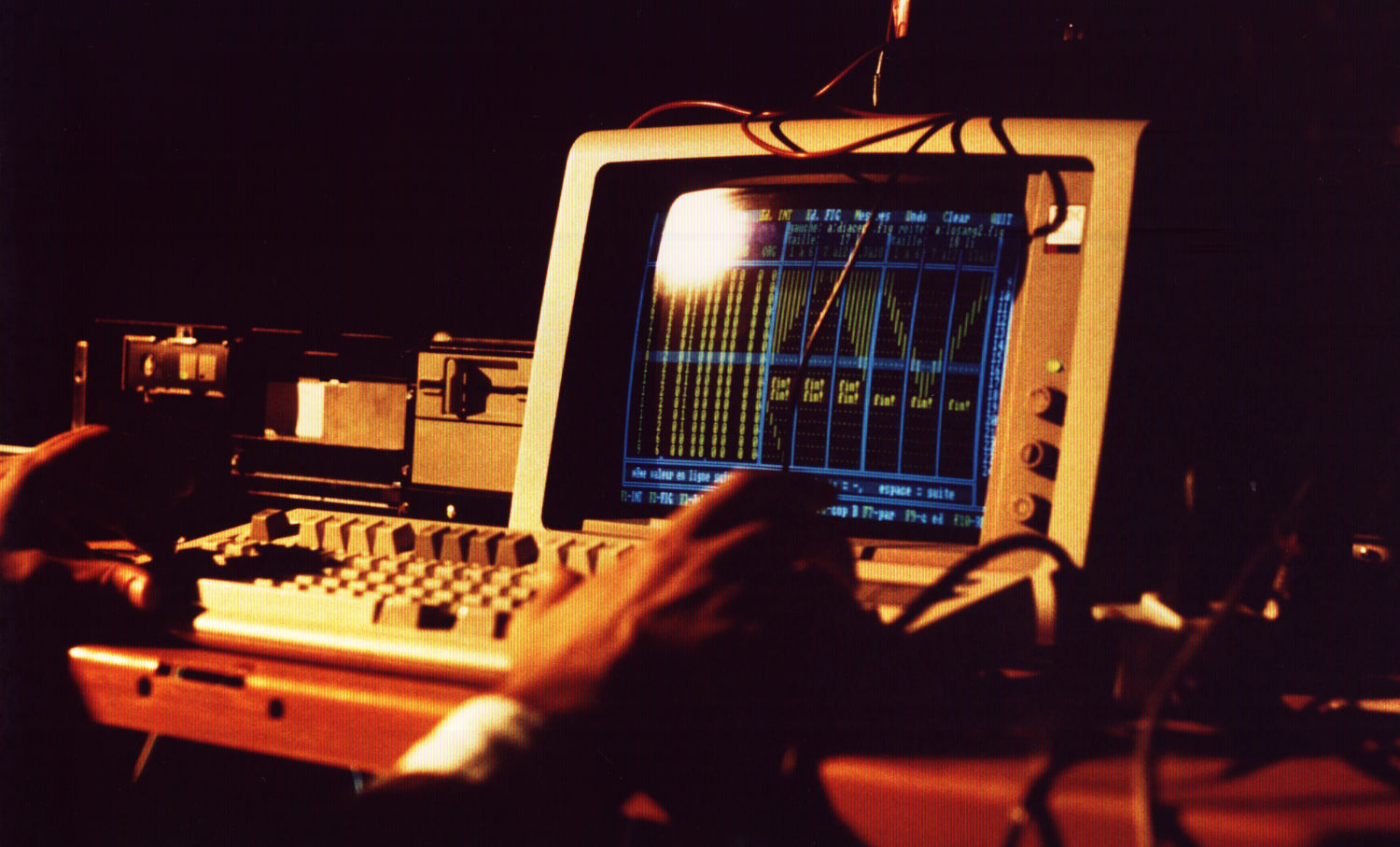

In 1985, my first compositions for Charlie in Bourges were exhausting to write. They were “raw” machine language.

0 - the lamp is off, 1 - the lamp is on. At 100 frames per second, you need to have strong nerves and a good supply of instant coffee on hand. In the basement of ASA Logiciels, we have all that. The first results from the 3D model seem worth it.

After a few days of sometimes acrobatic tinkering in Bourges, I was rewarded for my suffering in the open air in the basement of ASA.

When everything is in place, I look at Charlie from the café across the street: I like it, but maybe… Can I go further? For that, I need a convenient tool. Now that everything is working, more elaborate compositions are possible.

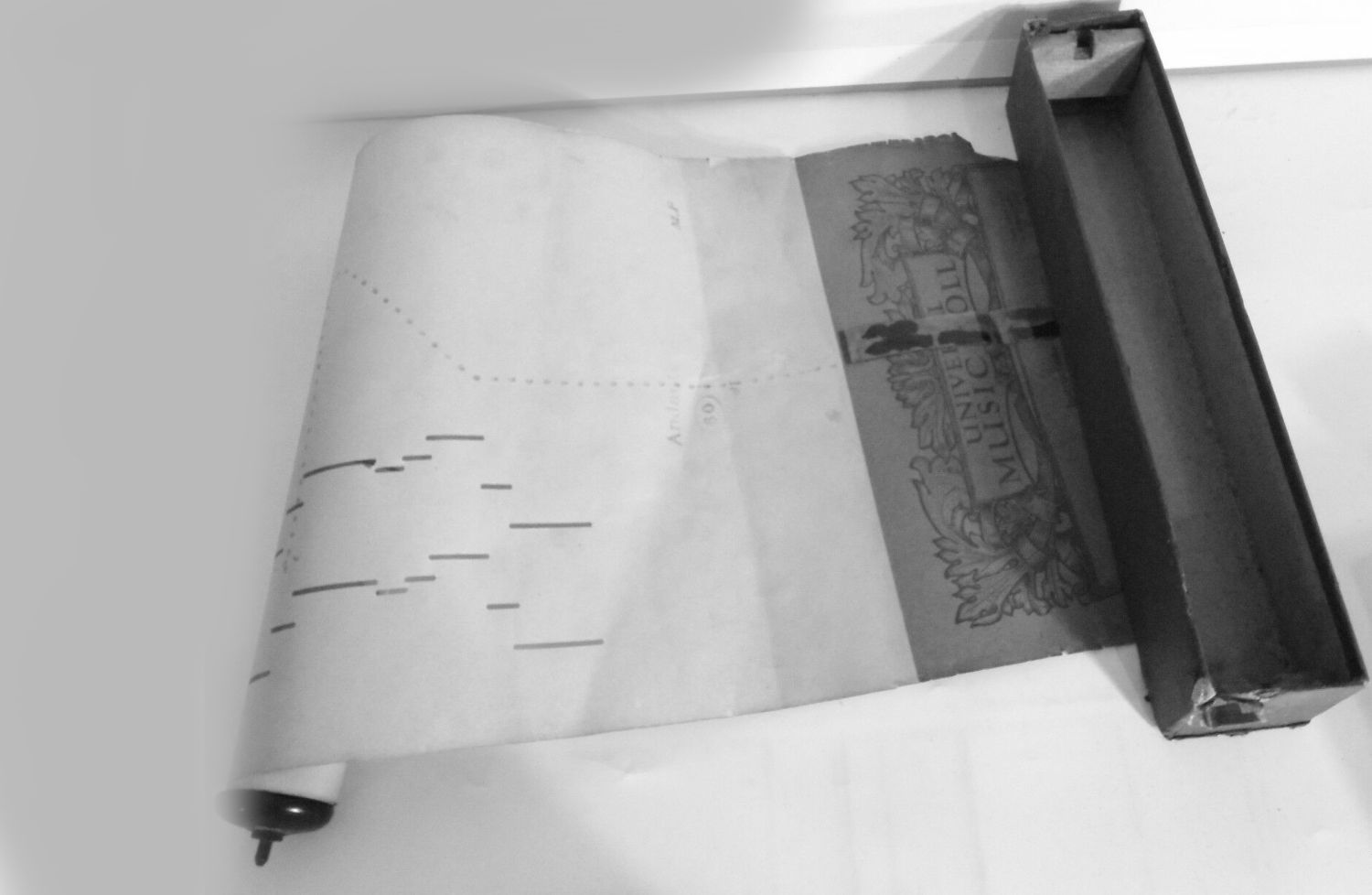

“Pianola” roll for mechanical piano - circa 1900

“Pianola” roll for mechanical piano - circa 1900

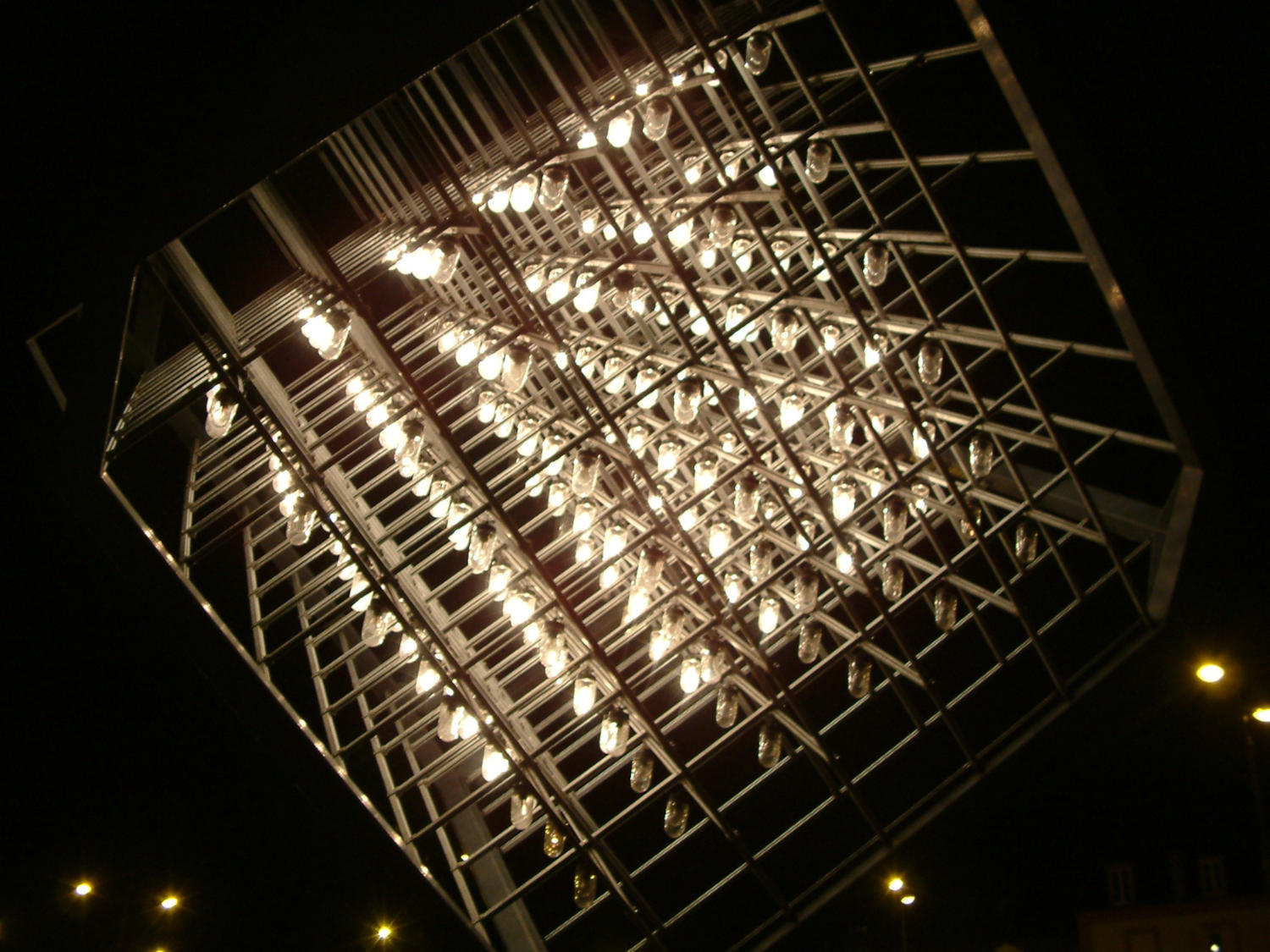

How do I do it? My first version is reminiscent of a mechanical piano roll unfolding on the screen. It’s not very flexible. I need a “light treatment,” like word processors. Nothing like that exists. Since Reims, when an idea comes to me, I write a new version. I try a bit of everything. My mistakes sometimes bring me something new, something unexpected. It’s a truly delightful feeling: having to write down your mistake so you don’t forget it.

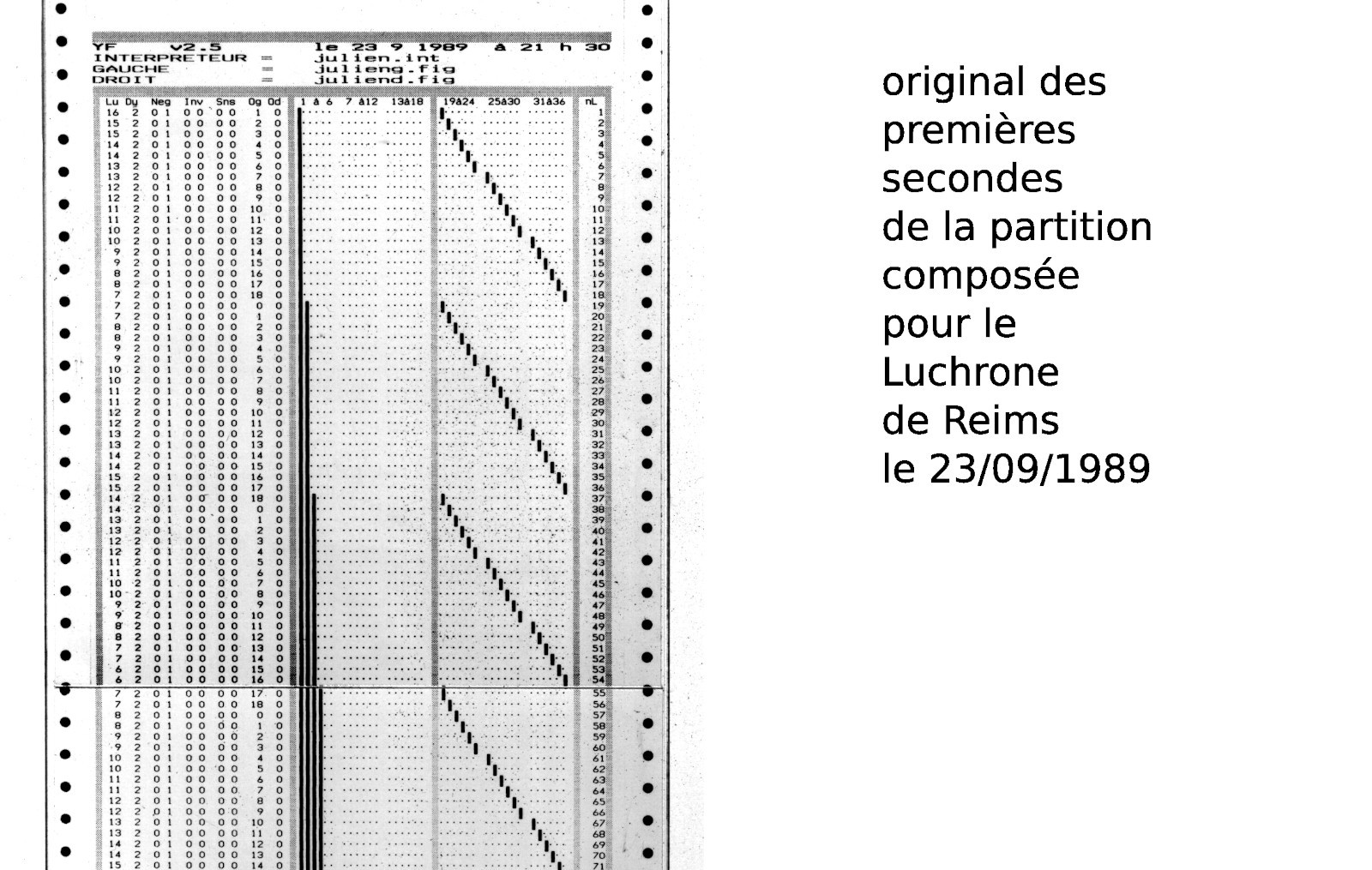

the original score presented to Mr. Falala, Mayor of Reims

the original score presented to Mr. Falala, Mayor of Reims

Writing code doesn’t cost much; it’s “the” detail that we artists need to consider. Unfortunately, I’m terrible at programming, whereas I’ve acquired some basic knowledge of electronics. And above all, alongside Francis Gernet, my programmer friends at ASA are there to suggest the three lines of code that save the day at just the right time.

the screen shows the same layout as the paper

the screen shows the same layout as the paper

Written in Delphi, the first version of my “light treatment” was used to compose the inaugural score for the Coquille de Reims in 1989. Since then, I have continued to improve my program by getting closer to the music that is my source of inspiration.

listen to the musicians

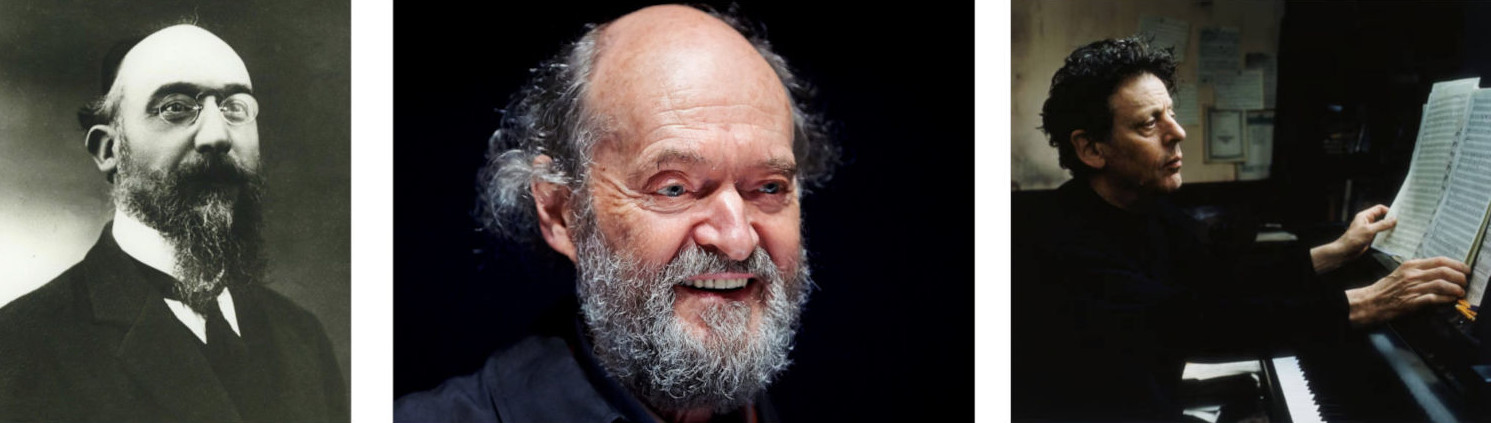

Erik Satie, Arvo Pärt, and Philip Glass

Erik Satie, Arvo Pärt, and Philip Glass

Among contemporary artists, I am more interested in minimalist music than in atonal or serial explorations. Paradoxically, I prefer a more classical, stripped-down style to musique concrète, which uses computers like me.

Philip Glass often draws inspiration from Erik Satie

In the whirlwind of contemporary music, I appreciate music that “doesn’t make noise.” Minimalists like Steve Reich, John Adams, Arvo Pärt, and especially Philip Glass seem more modern to me than revolutionary attempts, since the 1990s, the avant-garde has no longer been a requirement in art.

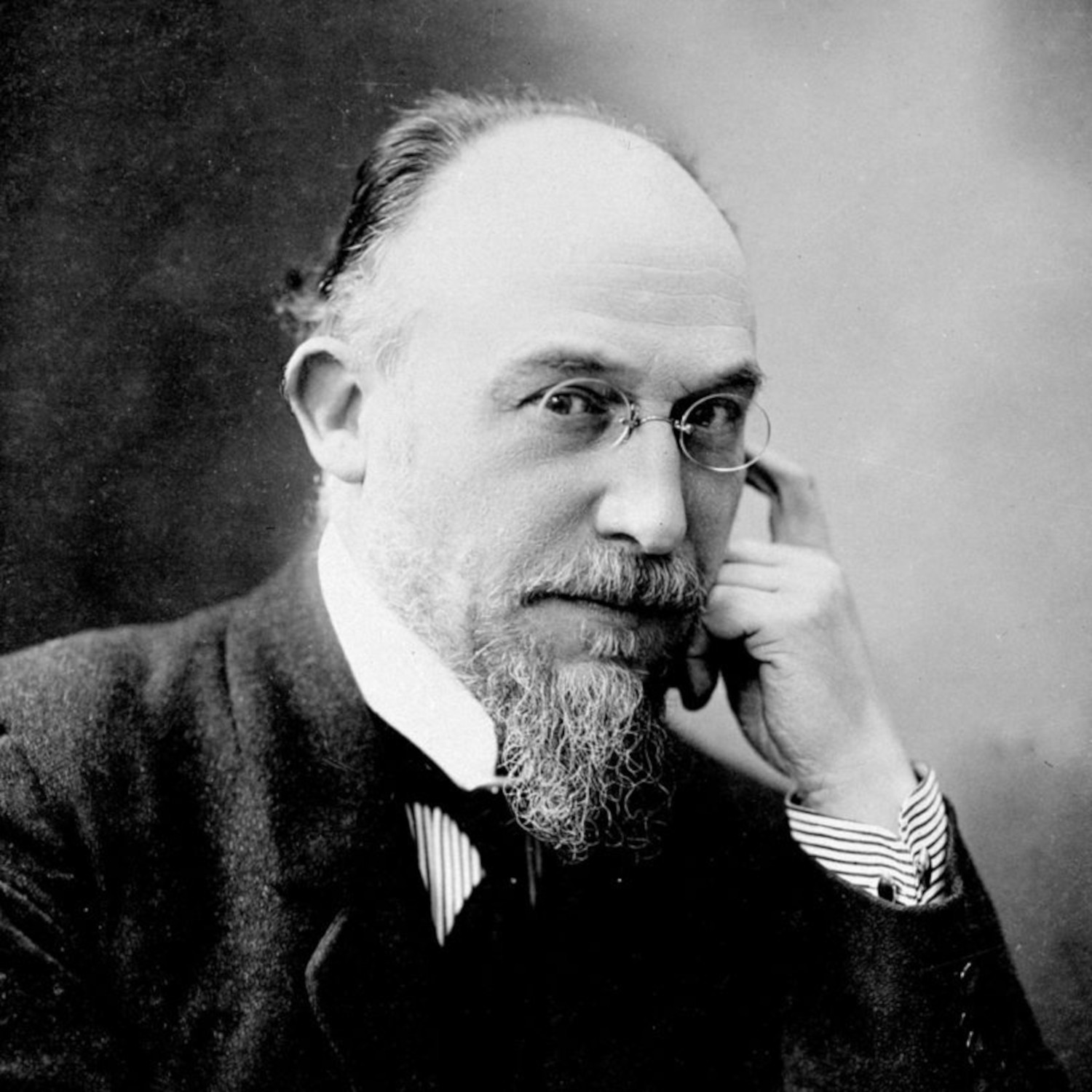

Ianis Xenakis “Metastasis” - 1954

These musicians prefer classical instruments over synthesizers. More than the instrumentation, it’s the way of constructing, of composing; It’s the atmosphere they create that matters to me and moves me.

Philip Glass at Carnegie Hall - 2022

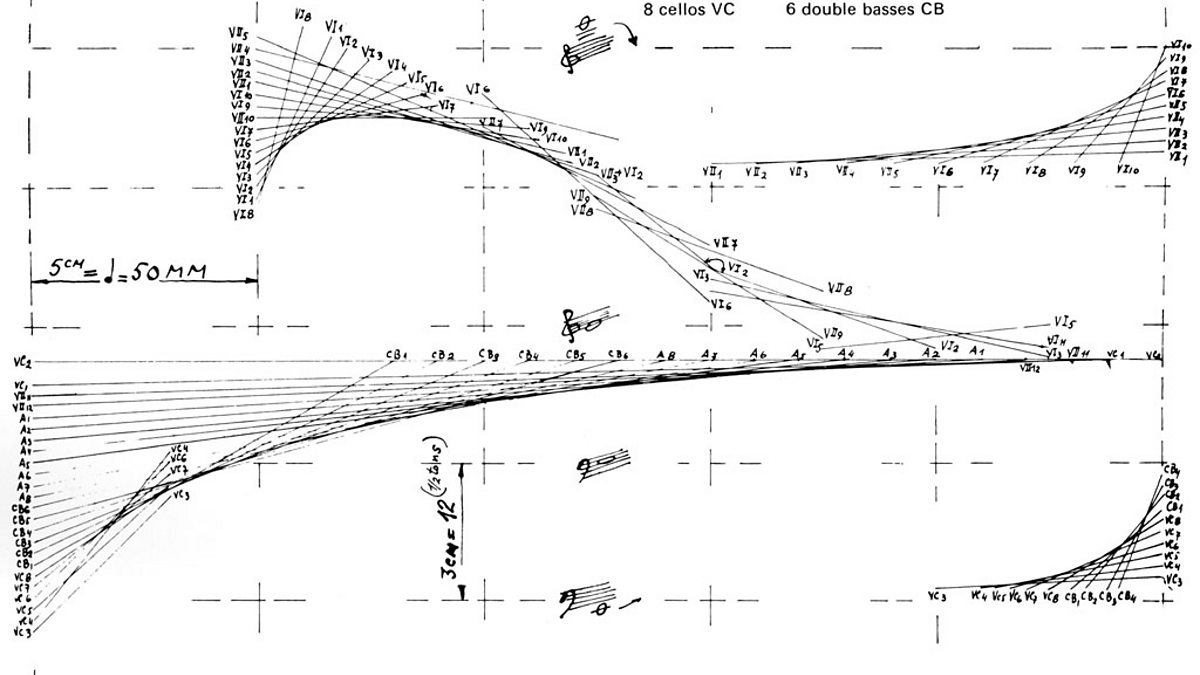

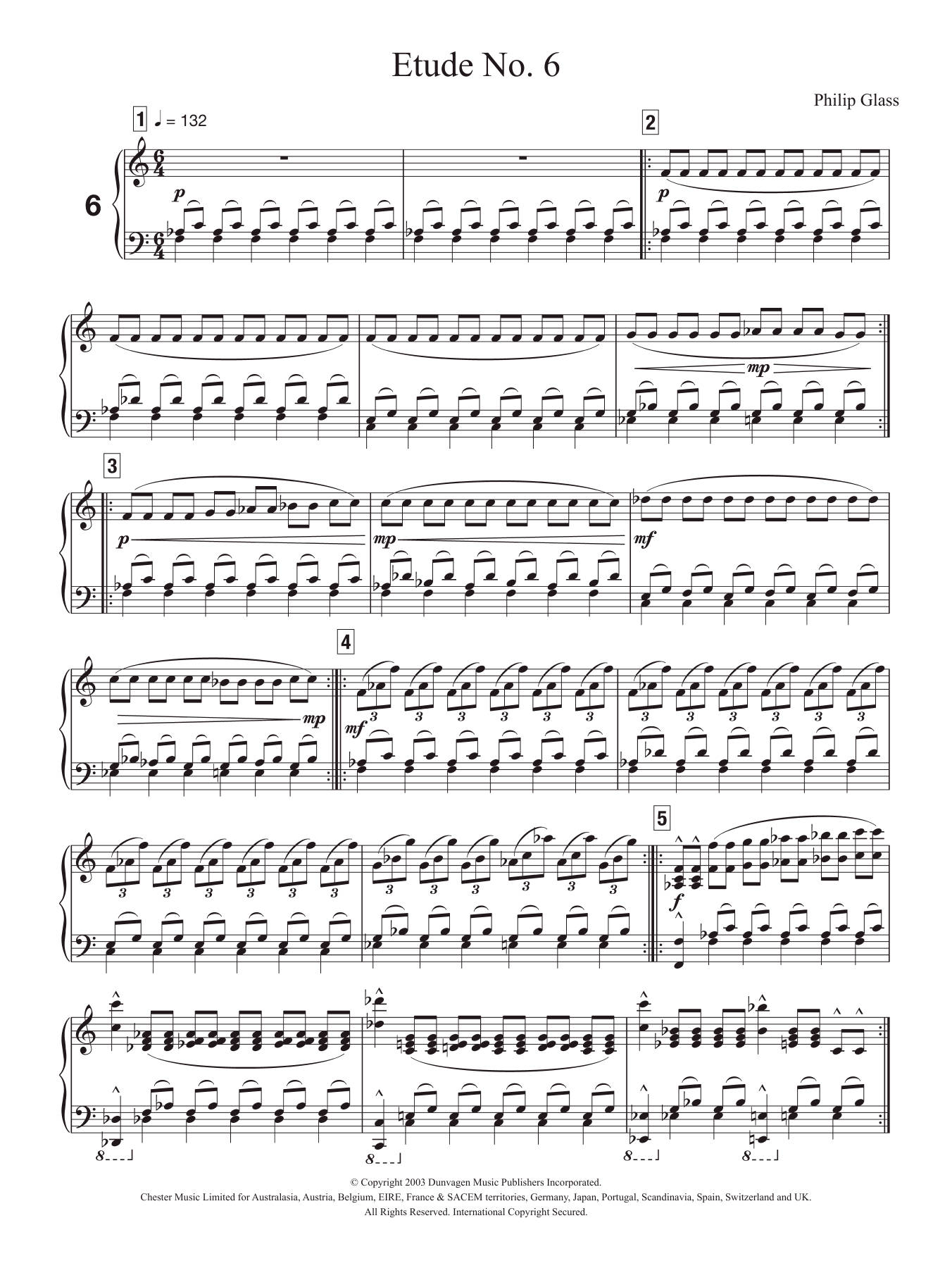

He wasn’t very present on France Musique, but in Aix, Philip Glass’s rare LPs circulated among students. The score demonstrates the rhythmic construction, both powerful and light, that is a constant in his work.

Philip Glass Study No. 6 - 2003

in Olafsson’s sensitive interpretation

Philip Glass Study No. 6 - 2003

in Olafsson’s sensitive interpretation

Johan Joseph Fux, a contemporary theorist of Bach, will be sponsoring my current treatment of light.